A Man for All Ages: Dr. Steven B. Harris

Few have influenced cryonics and its history more than Steve Harris. His work in- and outside of cryonics spans many disciplines across decades, reaching far corners of interest and exploration.

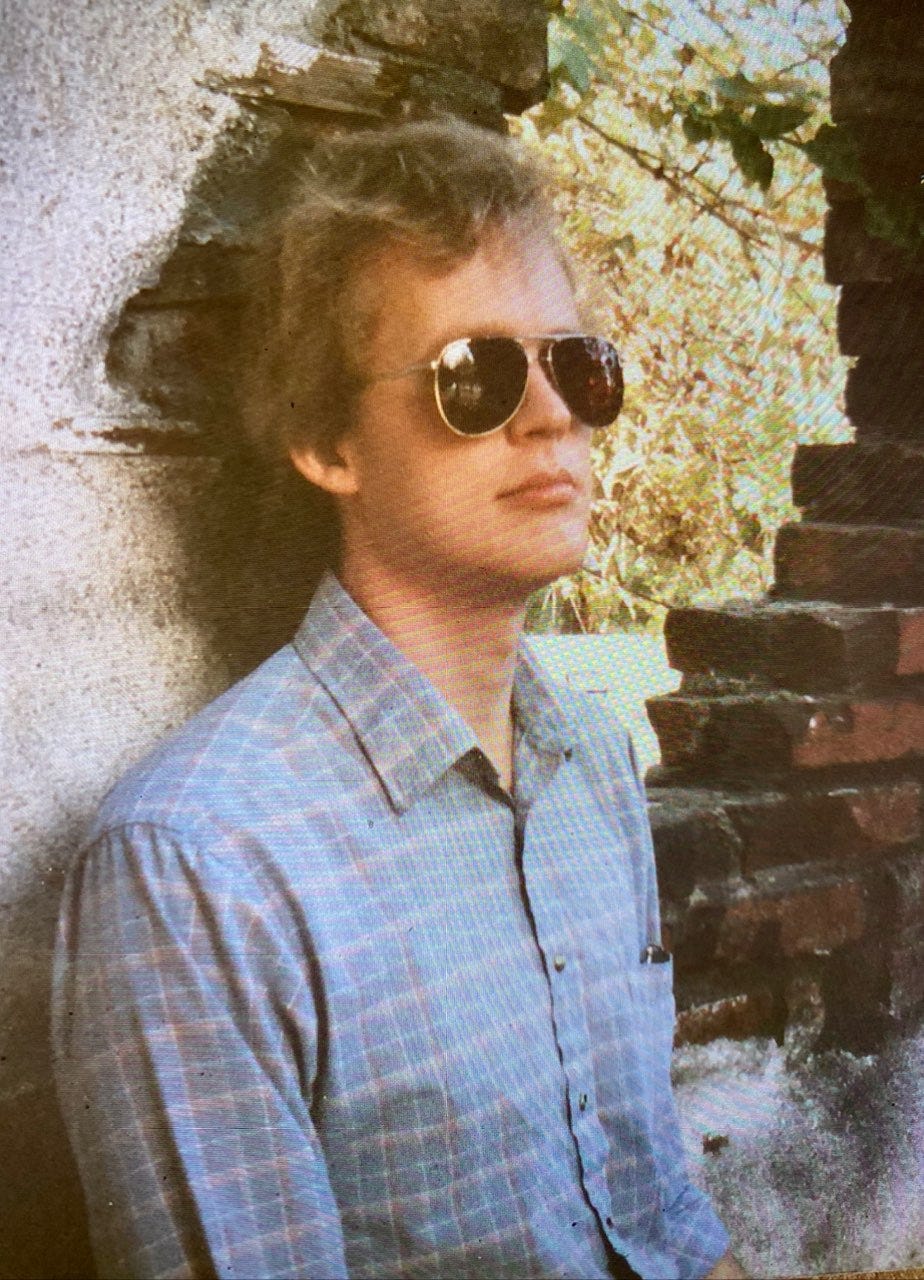

Dr. Steve Harris, April 7, 1991

By Brian Wowk, PhD

Steven B. Harris, MD, was cryopreserved by Alcor in November of this year, 2023, after an unattended cardiac arrest. It’s difficult to imagine a facet of cryonics that wasn’t touched by Steve Harris. From standbys to stabilization protocols, cooling technology, cryoprotectant formulations, even early ideas for intermediate temperature storage, Steve influenced all of it. His work was especially crucial for protecting the brain from ischemic injury, injury caused by stopped blood circulation.

He was deeply involved in cryonics for almost 40 years, with contributions ranging from technical, legal, social, and scholarly, and just plain helping with anything whenever asked. His titles and roles in cryonics are too numerous to list, the last formal one being Chief Medical Advisor of Alcor until 2018. He is among the most influential contributors to the field of cryonics whose work is now integral to the practice.

People who know Steve from his work in cryonics and related sciences may not be aware of his other interests and contributions to fields such as aging research, nutraceuticals, pharmaceutical formulation, rational skepticism (which cryonics critics might consider ironic), humanism, and novel ideas ranging across radiation protection, interstellar travel, hyperloop engineering, and scuba diving equipment. He’s a true polymath, with knowledge spanning sciences and humanities greater than anyone I’ve ever known. He could and did correct tenured physics professors on the spin of particular subatomic particles at social gatherings.

Steven B. Harris was born in Springville, Utah, in 1957. His family was Mormon, although as an adult he self-identified as an agnostic humanist. He has an adopted sister and adopted brother. He always characterized his childhood as a happy one.

He obtained an undergraduate degree in Chemistry from Brigham Young University, and a medical degree from the University of Utah and Brigham Young University. He did a fellowship in gerontology and geriatric medicine at the UCLA School of Medicine, and was a biogerontology Research Fellow at UCLA until 1993. He’s board certified in internal medicine, and practiced and taught geriatric medicine at University of Utah Medical School. He was also one of the founders of the research company, 21st Century Medicine, Inc. (21CM), and would later become the Managing Director and Director of Research of Critical Care Research, Inc. (CCR), a 21CM spin-off company specializing in brain resuscitation and therapeutic hypothermia.

Steve’s contact with cryonics began in 1986, the same year he moved to Los Angeles to study and work in the laboratory of aging researcher, Roy Walford, at UCLA. Alcor President, Mike Darwin, noticed contributions that Steve had made to the libertarian magazine, Claustrophobia, criticizing the then-popular free radical theory of aging and ingestion of antioxidant chemicals to slow aging. Mike asked for permission to reproduce in Alcor’s Cryonics magazine an article that Steve wrote on the subject.

Mike also invited Steve to attend one of the canine hypothermia experiments being conducted at Jerry Leaf’s company, CryoVita, Inc. CryoVita shared facilities with Alcor in Fullerton, California. Coincidentally, Jerry Leaf also worked at UCLA Medical School, in the cardiac preservation laboratory of Gerald Buckberg. The CryoVita hypothermia studies from 1984 to 1987 were the experiments that led to the development of the MHP2 blood substitute solution, still used in cryonics today. Years later, Steve would speak about how profoundly he was affected by seeing recovery of large mammals after hours of cold lifelessness a few degrees above freezing. It was a dramatic demonstration of the counter-intuitive notion that metabolism can be non-lethally interrupted, or that prolonged clinical death is reversible, an idea that cryonics depends on.

Steve became a semi-regular contributor to Cryonics magazine, and a medical consultant for Alcor. He worked in Alcor’s operating room on his first cryonics case, A-1133, in June of 1987. Although not present for it, he consulted for A-1082, the Dora Kent case in December 1987, a case that became problematic because Alcor’s facility was used for pre-mortem care. (Present cryonics practice is to minimize involvement of cryonics personnel or facilities in medical care before cryopreservation.) Despite the sensational publicity of the case causing difficulty for Steve, he continued helping Alcor with cryonics cases. When Alcor was falsely accused by the Riverside County Coroner and UCLA Police of possessing stolen equipment with UCLA property stickers (which Alcor couldn’t disprove because the Coroner confiscated Alcor’s records), it was Steve who industriously searched records at UCLA to find the surplus equipment sales records that exonerated Alcor. This was just one of many times when Steve went to great lengths to help cryonics organizations, cryonics patients, and sometimes living members of cryonics organizations with medical problems, large or small. Steve and his people were principally responsible for conceiving and organizing a novel combination of intra-arterial chemotherapy and proton radiotherapy that saved Saul Kent’s life in the year 2000.

1993 was a tumultuous year in cryonics. A contingent of Alcor members, including Steve Harris, left Alcor to start another cryonics membership organization called the CryoCare Foundation (not to be confused with the Cryocare Equipment Company, a dewar manufacturer in the 1960s). CryoCare operated until the turn of the century when the rift with Alcor healed, and CryoCare patients were moved to Alcor.

In 1993, Saul Kent, Paul Wakfer, Mike Darwin, Steve Harris and others also started the mainstream medical research company, 21st Century Medicine, Inc. (21CM). 21CM assumed the intellectual property and equipment of Jerry Leaf’s company, CryoVita, Jerry having been cryopreserved in 1991. The initial focus of 21CM was brain resuscitation after cardiac arrest. Darwin and Harris with Sandra Russell and Joan O’Farrell developed a protocol that allowed dogs to recover with full health and normal brain function after 16 minutes of stopped blood circulation at normal body temperature. This research fed into protocols for stabilizing cryonics patients after cardiac arrest.

In the late 1990s, Mike Darwin and Steve Harris also invented “liquid ventilation” for rapid induction of hypothermia, described in more detail below. Steve continued development of liquid ventilation into the 2000s, eventually heading the company Critical Care Research, Inc. (CCR). CCR was spun off from 21CM after 21CM moved to other locations to accommodate its Cryobiology Division. CCR also did pharmaceutical formulation research. Steve also did ultra-profound (a technical term) hypothermia research in the CryoVita tradition intermittently in collaboration with 21CM until CCR was closed by its owners in 2021.

Aging Research

Steve studied and researched gerontology (the science of aging) at UCLA and also studied and practiced geriatrics (the medicine of aging). A list of his gerontology work and other scientific publications is available on his ResearchGate page. He was an early member of the Gerontology Research Group. He was an editor of the book, “The Future of Aging: Pathways to Human Life Extension,” in 2010. Steve was a critic of what he called the “One Hoss Shay” philosophy of gerontology, which was keeping everything operating reasonably well so that it could all lethally fail at once at some socially defined time, which was just fine. He didn’t think that was fine.

Brain Resuscitation

By the early 1990s, the laboratory of Peter Safar (the inventor of CPR) at the University of Pittsburgh had shown that the usual 4 to 6 minute window for brain recovery after cardiac arrest could be extended up to 13 minutes in dogs by restarting blood circulation with cardiopulmonary bypass to induce temporary post-resuscitation hypothermia, increased blood pressure, and dilution of blood to reduce blood viscosity and blood cell concentration while the brain recovered. Tests of individual drugs to improve brain resuscitation outcomes were not as successful, even when the agents tested had a good theoretical basis for mitigating ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Mike Darwin and Steve Harris hypothesized that the multi-factorial nature of ischemia-reperfusion injury meant that agents couldn’t be tested in isolation with any expectation of success. Multiple drugs needed to be administered to address multiple injury mechanisms. They undertook a series of experiments at 21CM in the mid-1990s using combinations of pharmaceuticals administered after intervals of cardiac arrest at normal body temperature. With these medications, and mild post-resuscitation hypothermia, they were able to recover dogs with normal brain function after more than 16 minutes of stopped blood circulation at normal body temperature. Steve Harris made particular contributions in recognizing and mitigating the role of inflammation in ischemia-reperfusion injury of the brain (Cryonics, 1st Qtr. 1999, page 9).

The details of this heterogeneous series of experiments were unfortunately never published. A decade later, Steve did generously allow Alcor to publish a summary of them in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences as part of a scientific argument for the utility of human cryopreservation (cryonics) when begun after clinical death.

Results of this research found their way into cryonics stabilization protocols that are still used today. The custom-formulated emulsion of lipophilic antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents called “Vital-Oxy” is a notable example.

Quantification of Ischemic Injury in Cryonics

Steve pioneered the idea of quantifying ischemic injury (injury accumulated during stopped blood circulation) during cryonics cases. Motivated by a suggestion by Michael Perry (Cryonics, 2nd Qtr., 1996, page 21) that the Q10 rule of biology could be used to “weight” ischemic time by body temperature, Steve proposed a measure in 2003 called E-HIT (Equivalent Homeothermic Ischemic Time). The concept was that accumulated ischemic injury as a patient cooled after cardiac arrest, depending on cryonics stabilization or lack thereof, could be expressed as equivalent to a certain length of time spent at normal body temperature without blood circulation. The lower the E-HIT, the less injured the patient. An ideal E-HIT would be a small number of minutes between cardiac arrest and commencement of cryonics stabilization procedures, with any additional E-HIT time being a measure of inadequacy of stabilization logistics, procedures, or technology. In 2020 Mike Perry and Aschwin de Wolf further refined E-HIT into S-MIX (Standardized Measure of Ischemic Exposure), now used to quantitatively analyze cryonics cases.

Liquid Ventilation

The known benefits of post-resuscitation hypothermia for brain recovery after cardiac arrest were often difficult to achieve in clinical medicine because of the difficulty of rapidly cooling a cardiac arrest victim after resuscitation. In the late 1990s, Mike Darwin and Steve Harris invented the idea of using liquid breathing as a way of rapidly cooling the human body. By using the lungs as a heat exchanger, with the resuscitated heart able to pump cold blood from the lungs through the rest of the body, liquid ventilation could cool cardiac arrest victims almost as fast as heart-lung bypass machines without need for surgery. They showed this in a 2001 paper in Resuscitation.

Total liquid ventilation with perfluorocarbons had been demonstrated for purposes other than cooling since the work of Leland Clark and Frank Gollan in the 1960s. Perfluorocarbon lung lavage had also been used clinically for treatment of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). However there was a great deal of research and development by Mike Darwin and Steve Harris, and later Steve and his people at CCR, to get liquid ventilation working effectively and without lung injury in the heat exchange application. Details included infusion timing, liquid-gas ratio, and fluorocarbon composition, balancing all the considerations of viscosity, freezing point, and vapor pressure. Too high a vapor pressure damaged lungs, while too low a vapor pressure caused post-procedure pneumonia from residual fluorocarbon remaining in lungs for too long. No one in the world acquired more knowledge of these details than Steve Harris. The combination of the closing of his company, Steve’s health (now including cryopreservation), and evolving concerns about environmental persistence of perfluorocarbons may mean the end of liquid ventilation as a promising rapid cooling method in clinical medicine, although equipment prototype testing for cryonics applications continues.

The cryonics application of liquid ventilation has its own issues requiring further research. Given the expected magnitude of cryopreservation injury to lungs, there is more flexibility for the composition of the heat exchange liquid in cryonics than clinical medicine. However the need for external chest compressions to circulate blood instead of a beating heart makes the cryonics application more difficult than post-resuscitation mild hypothermia. Cooling rates are slower without a beating heart, and target cooling temperatures are much colder in cryonics than therapeutic hypothermia. Research on the cryonics application had only just begun in recent years, with human clinical cryonics trials being the next step.

Novel Cryoprotectants

Steve’s knowledge of chemistry contributed to brainstorming novel cryoprotectants, one of which (3-methoxy-1,2-propanediol) is now an anchor ingredient in the M22 vitrification solution used in mainstream organ cryopreservation research and cryonics. I still remember looking at that molecule with Steve and Houston Westfall in a Sigma chemical catalog in a hotel room in Las Vegas in December, 1996.

Ice Blockers

In 1998 Steve observed that the spacing of hydroxyl groups in the molecule 1,3-propanediol was similar to the repeat distance of hydrophilic groups on certain antifreeze proteins. This inspired pulling a bottle of the water-soluble polymer, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), off a shelf at 21st Century Medicine and testing it for ice suppression activity because PVA structurally resembled polymerized 1,3-propanediol. PVA was found to be effective at enhancing vitrification of cryoprotectant solutions, even at concentrations far below that of an ordinary cryoprotectant. With subsequent optimization and synthesis methods pioneered by Eugen Leitl, this discovery became 21st Century Medicine’s “X-1000 ice blocker,” now an important ingredient of vitrification solutions used in both mainstream organ cryopreservation research and cryonics. Steve and his chemist at CCR, Nick Huang, later made additional contributions to the study of ice blockers by synthesizing PVA variants with fluorescent ligands and different polymer end groups.

Pharmaceutical and Nutraceutical Research

Steve and CCR chemist, Nick Huang, hold patents in many countries for a novel high concentration decomposition-resistant emulsion of propofol anesthetic. Their emulsion technology makes particles so small that their propofol formulation is a transparent liquid instead of milky. A study was published on its use in veterinary medicine.

Steve also did human clinical trials of coenzyme Q10 capsules containing ubiquinol emulsified by his technology, finding superior bioavailability. As often happens in business, he wasn’t able to bring this product to market for reasons unrelated to efficacy.

Cryonics Magazine

In his younger years, Steve wrote many articles and letters to Alcor’s Cryonics magazine. Sometimes they were about health, other times technical or legal matters. Once, after Alcor published technical details about a new piece of equipment built by staff, Steve wrote a letter with a revised electrical schematic for an improved power supply. Alcor published the letter and Hugh Hixon thanked Steve, acknowledging the substantial improvement!

Below is a partial list of Steve’s most memorable articles, starting with his first contribution.

Antioxidants and Aging: Thirty Years of Uncontrolled Experiments and Five Years of Foolishness

Cryonics, April, 1986 (reprinted from Claustrophobia magazine)

Will Cryonics Work? Examining the Probabilities

Cryonics, May 1989

Binary Statutes, Analog World: Burke’s Paradox and the Law

Cryonics, June 1989

A Few Thoughts on the Dead Ant Heap and Our Mechanical Society

Cryonics, April 1990

The Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Dead

Cryonics, September 1990 (reprinted from Skeptic magazine)

Lovecraft, Scientific Horror, Alienation, and Cryonics

Cryonics, October, 1992

The Return of the Krell Machine: Nanotechnology, the Singularity, and the Empty Planet Syndrome

Cryonics, 4th Qtr. 2001 (reprinted from Skeptic magazine)

The last contribution is particularly dark. In hindsight, it might have marked the beginning of the end of Steve’s youth. With greater age and experience, the difference between what’s theoretically possible and the actual trajectory of human affairs becomes larger and more visible. There may be no endeavor in history for which that difference is larger than cryonics. I think Steve felt the weight of that in his later years, and it took a toll. He became less involved, more reactive than proactive. He would always pick up the phone and help when asked, but people asked less and less as time went on, and I think that affected him too.

Rational Skepticism and Humanism

Steve was active in the community of rational skepticism, published in Michael Shermer’s Skeptic magazine, and spoke at skeptic events about topics such as “Fear of Science & Technology.” He especially took issue with homeopathy, vaccine denialism, and AIDS denialism.

As incredible as it seems now, there were credentialed scientists and physicians in the 1980s and as late as the 1990s who vocally argued that the HIV virus didn’t cause AIDS, much to the detriment of public health. Steve published a book chapter and a series of articles in Skeptic magazine criticizing this view. He also debated this issue on Usenet, predicting that protease inhibitors would treat and prevent AIDS with high effectiveness. He wrote that this would finally shut down remaining debate about whether HIV caused AIDS. At the turn of the century, that’s exactly what happened.

In 1989, Steve introduced the secular humanist community to cryonics in an article published in Free Inquiry magazine entitled, “Many are cold but few are frozen: a humanist looks at cryonics.” The article is even indexed by PubMed. My recollection is that it wasn’t well received by Free Inquiry readers, probably because for historical reasons self-identifying secular humanists tend to be more egalitarian than individualist.

UseNet and Wikipedia

Steve shared his literally encyclopedic knowledge with the world. He made more than 38,000 additions and edits to Wikipedia, working under his own name with Wikipedia userid Sbharris. He maintained a particular interest in the history of the American Old West. Anyone wondering what Steve thought about the state of the cryonics article on Wikipedia can peruse his comments on the article Talk page archives.

Steve didn’t suffer fools gladly, and had acerbic debating style laced with wit. It was a tradition that went back to his days on Usenet. Many Usenet threads that Steve participated in were elevated to archive status on yarchive.net, a website specializing in archiving Usenet articles “posted by people who have a well-deserved reputation for a high level of accuracy.” Some of those threads include brain resuscitation, free radicals, critiques of anti-vaxxers, vitamin E, and science reporting in newspapers. Steve also contributed to the original CryoNet cryonics email discussion list.

Burning Man

Steve and his life partner, Sandra Russell, attended Burning Man regularly for a stretch of years. I think Steve enjoyed the zaniness of it all. He once told me of a laser someone brought in on the back of a truck. It was so powerful it visibly shone across the Nevada valley floor making a spot on a mountain more than ten miles away. He invited me to throw in to build a laser like that. I declined, figuring that the Department of Defense might take issue with it.

Scuba Diving

Steve dreamed of scuba diving as a kid watching the TV show, Sea Hunt. Steve and Sandra would dive deeper and more widely across the world than Lloyd Bridges ever did. It was his passion.

He even invented a new type of scuba regulator that allowed a diver to rebreathe each breath of air once. As a medical physiologist, he knew the CO2 buildup from one rebreathe would be safe, oxygen would remain ample, and bottom time would be extended, especially for nitrox diving. Unfortunately diving companies wouldn’t agree to a non-disclosure agreement, and he couldn’t afford to patent it before pitching it, so that was where the idea ended.

A Generous and Caring Man

Steve’s been a scholar, gentleman, and good friend ever since first meeting him online in 1986. Sandra and Steve were Aunt and Uncle to my kids growing up in Southern California. Participants in sometimes irate debates with Steve might not believe it, but he would give the shirt off his back to help people. I heard indirectly that he even helped some Alcor members financially despite being of no great means himself.

Recently another friend privately mused about different types of personal motivation he had seen over decades of cryonics activism. About one particular group of individuals, he said "their heart is in the right place.” He was speaking about dedication to procedures and practices consistent with technical principles of cryonics, but thinking about Steve gave the observation extra poignancy. Steve’s heart was in the right place in every sense. He just didn’t have the patience for politics. Steve once wrote, “All of this makes completely comprehensible why bureaucrats, when they seize total power, kill the intellectuals first."

In 1999 a Usenet poster predicted (sarcastically?) that Steve and another physician whom Steve was tediously debating in the sci.med group would someday receive an award “recognizing the help they have given others”. Steve responded seriously:

“Why thank you, and I'm glad you think so. However, this is not the way the universe works. Rather, one is generally gently punished for one's "good deeds," (ie, altruistic deeds) naturally because one has by definition spent time on them, instead of bettering one's own lot. That's the road to bitterness. I remember that fact, and live accordingly. Which is to say, I live my life mostly a day at a time, and try to keep my rewards and vacations ever caught up. The idea being that whenever I reach the end-- which, you never know, could be any time-- I won't have much owing or owed. Or much experience I wanted to have, and missed. Since, as an agnostic, I very much suspect that the books will have to balance then, because after that, nothing will survive of me, except for those parts of my thought I manage to infect the world with. And perhaps my frozen (self) if the cryonics team isn't too (unprintable). Hopefully, when all is said and done, the world will be just a TAD better overall, than when I found it.”

Steve’s punishments for his good deeds ended up being more than gentle, but the world is better by more than a tad. Much more.

"Photo courtesy Brenda Peters."

Wow, what a deeply moving, solidly researched, and very personal article Brian Wowk has written about his friend and Cryonics activist Dr. Steven B. Harris!

I met Steve Harris a few times, and was impressed with his broad knowledge and dedication to the ideas of Cryonics. I did not know of his other interests, as outlined in this article.

The distinction between what is theoretically possible and the actual achievement of humanity is indeed a large gap. And, as I age, grow potentially wiser, but also more cynical, this distinction does indeed weigh more heavily in my mind.

We will miss Dr. Harris, and we have a realistic chance of interacting with his remarkable intellect in the future. Dr. Brian Wowk, thank you for the outstanding job you have done in this article.