Does Death Give Meaning to Life?

Spoiler: It does not

“The finitude of human life is a blessing for every human individual, whether he knows it or not.” – Leon Kass

“Be ashamed to die, until you have won some victory for humanity.” – Horace Mann

Why do some philosophers and other observers of the human condition claim that death gives meaning to life? Why would something gain in meaningfulness because it comes to an end? Normally, we think the opposite—that value lies in continuation, not cessation. In his book, The Case Against Death, Patrick Linden refers to this ironically as the Wise View. Prominent among the Wise Guys is Bernard Williams, former president of the President’s Council on Bioethics who provides the first quotation above. He also declares that “The desire to prolong youthfulness [is] an expression of a childish and narcissistic wish incompatible with devotion to posterity.”

Another Wise Guy, his sometime colleague, Francis Fukuyama, complains that old people “refuse to get out of the way” and has said that the government has the right to prevent people from living too long. Bioethicist Daniel Callahan tells us not to try to prolong lives. “A full human life is possible to achieve by 65. After 80, one’s death is still sad but not a tragedy; it is a tolerable death.” Speak for yourself, Daniel.

Suppose, for a moment, that Williams and Kass are correct in their claim. Is this an argument against life extension? No matter whether we live 300 years, 3000 years, or millions of years, we are not immortal. We expect that our life will come to an end eventually, even if we hope it is far, far into the future. If you believe it is, consider that even with the abolition of aging, you will not know how long you are going to live.

There is always some chance that you will be murdered, catastrophically damaged beyond repair in an accident, struck by an asteroid, or evaporated by a gamma ray burster. That implies that we could live for a million years and our lives could still be meaningful. Even if death is, for some odd reason, necessary for life to have meaning, in practice the argument is useless.

If the Wise Guys insist that it is the expectation of death that gives meaning to life, is life more meaningful or less if you believe you have almost no time left? Are our lives less meaningful today when we can expect to live 80 or 90 years than they were when we could expect to live 40 years? Does anyone really believe that the shorter-lived people of the past had more meaningful lives because they were shorter? Should we take a lesson from Logan’s Run and require everyone to die at 30 (or 21 in the book) to ensure a super-meaningful life? I think not.

The “death gives meaning to life” view has always seemed bizarre to me. How might we make sense of it? Bernard Williams attempts to make sense of this claim by likening a human life to a novel or movie. These have a dramatic structure that is shaped in part by its ending. (As biostasis advocates, perhaps we would be seen as striving for a sequel.) What kind of story is our life then? Is it a drama: A romance? Horror? Science fiction? To ask the question reveals how silly it is.

Life is not about one thing, one goal, one activity, one event. If we strain to make our lives fit the model of fiction, it would be more reasonable to see a life as more like an ongoing series. Even that is a stretch. Our lives are too messy to fit the mold of a novel or movie, or even a continuing series.

The Stoics are known for their acceptance of the inevitable and their ability to not rail against it and allow fighting against the inevitable to lead to frustration, fear, and unhappiness. We can probably find some variation in views between the Stoics. In the case of Seneca – one of the most readable of the ancients – we find the view that death is natural and not to be feared, but neither is it a source of life’s meaning. He claims that the value of life lies in how you live, not how long you live. (Why not both?)

Because death is certain, we should use our time well — focusing on virtue, reason, and inner freedom instead of wasting life in anxiety, greed, or distraction. That is, death clarifies values but does not create them. He would say death is a reminder, not a source of meaning. Seneca would not agree that immortality would make life empty or repetitive. Applying stoicism becomes tricky when we begin to have some realistic ability to postpone death. Regardless of how long we may live, it makes sense to live well and virtuously.

Death and other people

This discussion centers on the meaningfulness of an individual’s life and death to himself. If you are universally hated, your death will cause no loss to others, except perhaps economically. In practice, your death, my death, anyone’s death will cause grief for others. The dying process magnifies the emotional suffering of death. This is sometimes the reason extremely depressed or otherwise distressed people refrain from suicide. They understand the horrible emotional pain it will cause their loved ones. Whatever we decide regarding the meaningfulness of our life, we should include the feelings and plans of others in any calculation.

Lump of life fallacy

A related confusion underlies many objections to life extension: what I call the Lump of Life Fallacy. This fallacy assumes that there’s a fixed amount of things to do, experience, learn, and create —that after a certain number of years, one must run out of novelty or purpose. I base this on the “lump of labor fallacy” – the misconception that there is a finite amount of work to be done within an economy which can be distributed to create more or fewer jobs.

Williams and others have a related argument in addition to the idea that the end of life meaningfully structures lives. They claim that a greatly extended life would be boring. Apparently, they lack imagination and cannot think of activities to occupy them for decades or centuries. I suspect that most readers of this blog know of enough knowledge to learn, games to play, experiences to have, relationships to foster to last them for many decades. During that time, the world would change, providing us with fresh experiences and opportunities.

The lump of life view sees life as having a limited number of possible experiences, goals, projects, relationships. Live long enough and you run out of them and repeat them. But there is no reason to expect to run out – certainly not in any comprehensible time frame – and if you were eventually to repeat some, you may not remember the first time, or it will be so dim that it’s almost like new. In some far future, you could also deliberately prune memories to make an experience completely new again.

Modern philosophical views

It would be easy to form the impression that philosophers support the idea that death gives meaning to life. Reading Bernard Williams would certainly create that impression, as might perusal of Martin Heidegger’s thinking. Heidegger grants that death is not a moral good but claims that awareness of mortality forces “genuine” choice and facing one’s death enables “authentic living”. Therefore, death gives meaning not by enriching life emotionally, but by structuring existence and freeing us from inauthentic conformity. If you have a tough time making sense of that, welcome to the club.

More recent philosophers have espoused more plausible and sensible views. They have rejected the notion that death gives life meaning and do not accept that even a literally immortal life would necessarily lack meaning. These philosophers treat meaning as intrinsic to value and consciousness, not as a gift of mortality.

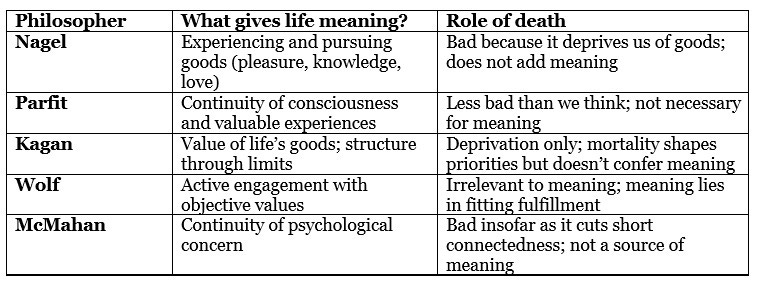

Among these are Thomas Nagel, Derek Parfit, Shelly Kagan, Susan Wolf, and Jeff McMahan — philosophers who converge on a more life-affirming consensus.

In our brief survey of more recent philosophers, let’s start with Thomas Nagel. He wrote on our topic in his essay “Death” in his book Mortal Questions (which also includes the classic “What is it like to be a bat?”). Nagel argues against the Epicurean position (that death isn’t bad for us because we don’t experience it). Death harms us not because of any unpleasant state, but because it deprives us of the goods of life.

Far from giving meaning to life, death removes meaning and value by depriving us of goods; immortality could be good if life stayed fulfilling. Meaning in life comes from living, not from the fact that life ends. It’s worse to die earlier than later because it means fewer experiences, projects, relationships, and pleasures. Given Nagel’s view, if we could live longer, we would be better off – and immortality would not, in itself, be meaningless or undesirable, provided life remained good.

Derek Parfit is another relatively famous and distinguished modern philosopher. My own doctoral dissertation was inspired by his remarkable book, Reasons and Persons. According to Parfit identity is not a “deep fact.” There is no underlying, unchanging self that persists through time. Instead, our identity consists of the psychological continuity resulting from close psychological connections between instances of us close together in time. On his view, we will care greatly about not dying in the near future because we will be closely psychologically connected to the person who dies. But in the future we are pondering, the more we will have changed and so the less death (or other misfortunes) matter.

Parfit does not argue that death is good, nor even that is not bad. He concludes that death is less bad than we think. “When I believe that my existence is such a further fact [that there is a deep self that continues or ceases], death seems to be the boundary of a rigid identity. When I lose this belief, death seems less bad.” Parfit agrees with Nagel in seeing death as a loss of experience but thinks that the fear of ceasing to exist loses much of its sting when one sees that there is no “inner self” that could have continued anyway.

Death deprives us of possible goods – what Nagel calls the deprivation thesis – and the fact that we die doesn’t create meaning. Meaning arises from the existence of value-bearing states (pleasure, knowledge, love, accomplishment) while we live. I think this is clearly right but I find that he goes too far in minimizing the significance of death based on his theory of personal identity or survival. Parfit seems to think that the loss of our projects matters less because other people may have the same or similar projects. But we are coherent selves and distinct from others. The fact (if it is) that one or more of my projects might be carried on by others in some form is small comfort. It is better than nothing but far worse than me living and pursuing my project personally.

Yale University philosopher Shelly Kagan delves into this topic in his 2012 book, Death. Kagan says that death is bad because it deprives us of future goods we could have enjoyed. If life is good, more of it would be better; if life is miserable, less of it may be good. There’s nothing logically incoherent about living forever if your life remains full of value. “It is the good parts of life that make life worth having. Death takes those away.” Instead, he argues that meaning comes from the contents of life — the projects, relationships, and values that make it good — not from the fact that it ends. It’s not that mortality gives life meaning, but that limited time influences how we choose what’s meaningful.

Susan Wolf, in Meaning in Life and Why It Matters (2010), doesn’t dwell on death at all — because for her, meaning arises from the relationship between subjective engagement and objective value. We find meaning when we are actively and lovingly engaged with things that are actually and objectively worth doing — art, science, relationships, moral causes, creation, discovery.

Similarly to Nagel and Kagan, for Wolf meaning depends on value-laden activity, not on lifespan. Whether you live for 50 years or 5,000, what matters is the quality and objectivity of what you’re engaged in. She writes: “Meaning arises when our love of something meets something worth loving.”

Jeff McMahan, especially in The Ethics of Killing (2002), builds directly on Parfit’s reductionism. He provides the “Time-Relative Interest” Apccount. This holds that the badness of death depends on how psychologically connected we are to our future self. A newborn, for example, has fewer developed connections to its future, so its death is less bad (in deprivation terms) than the death of an adult — because less is lost from the standpoint of psychological investment.

This view unites Parfit’s reductionist metaphysics with Nagel’s deprivation model: death matters not because of a metaphysical boundary, but because of the interrupted continuity of experience and concern. Meaning depends on the same continuity — on the projects, intentions, and memories that link a person’s past, present, and future. So meaning is temporal and psychological, not metaphysical or dependent on death. Death ends meaning; it doesn’t create it.

Summary: The Analytic Consensus

Modern analytical philosophers have reached something of a consensus:

Death is not what gives life meaning — it merely limits the scope of meaning.

Meaning arises from valuable experiences, projects, and connections, whether or not they end.

Immortality could be meaningful, provided that life retained novelty, engagement, and value.

Finitude may affect urgency and structure, but not value itself.

This modern analytic view diverges sharply from ancient, existentialist, and romantic notions that we “need” death for depth or significance. Instead, it treats meaning as intrinsic to value and consciousness, not as a gift of mortality.

Where They All Converge

Final thoughts

I would say that meaning cannot be given by external beings or institutions, although we can choose to commit ourselves to a way of life, a belief system, or a social or political organization. These do not automatically bestow meaning on our lives. Our participation may be meaningful to others because we are working to further a goal they share. But if this goal is imposed on us, it is unlikely to be meaningful or satisfying. Only if we choose this institution, system, or type of activity does it make it personal and a source of meaning and purpose.

Meaning is personal, not objective or external. Nothing outside us can force meaning on us; that would be mere compulsion. Freedom and autonomy are important in creating meaning through our choices.

Not only is the view that death gives life meaning wrong, it is backward. As the above philosophers note each in their way, death cuts off the things that make life meaningful. Other things being equal, longer lives would – or could – be more meaningful. Every action would have a longer future trajectory to echo through, influencing more lives, more outcomes, and more understanding. You can build on each action and reach greater heights. Your life can amount to more.

Death adds nothing to meaning, it only limits it. On the contrary, death often brings grief and loss. Removing the fear of death could allow individuals to focus more fully on living fulfilling lives, free from existential anxiety.

We want to actually accomplish things and not merely feel good. Meaning is related to the pursuit of our values including love, creativity, achievement, understanding, and contribution to human flourishing. Meaning is personal and not dependent on time. Many people derive meaning from ongoing projects, relationships, or contributions to humanity that would not lose value with a longer lifespan. A meaningful life is not inherently tied to its brevity; rather, it depends on how life is lived and valued.

With an unlimited lifespan, individuals would be able to make more significant contributions to humanity and the universe. Long-term projects, like interstellar exploration or solving complex scientific problems, could become feasible. Extended lifespans could lead to cumulative wisdom, better decision-making, and stronger cultural and societal foundations. An unlimited lifespan could lead to a reevaluation of morality, purpose, and values, deepening humanity’s understanding of itself. Ethical systems could evolve to focus on long-term well-being and sustainability. Individuals could explore existential questions in greater depth without the pressure of mortality.

I wrote on this topic 34 years ago in “Meaning and Mortality.” In Cryonics #127, Vol.12, No.2, February 1991.

Additional thoughts

Herbert Marcuse is not a philosopher I hold in high esteem but his views on death are sensible. Aschwin de Wolf wrote about them here.

Discussions of meaning and death often talk about boredom, as if it were an inevitable consequence of immortality – or even indefinite lifespans. I have covered this elsewhere, as has Aschwin de Wolf who makes related points and notes many activities have intrinsic value that do not vanish with repetition.

People who argued that death gives life meaning always struck me as lacking imagination.

Regardless of their many and varied justifications for this belief (as you’ve outlined) these people will universally look dumbfounded when asked what they’d personally do even with, say, thousand year lifespans.