Maximum Lifespan

Will the rising trend continue?

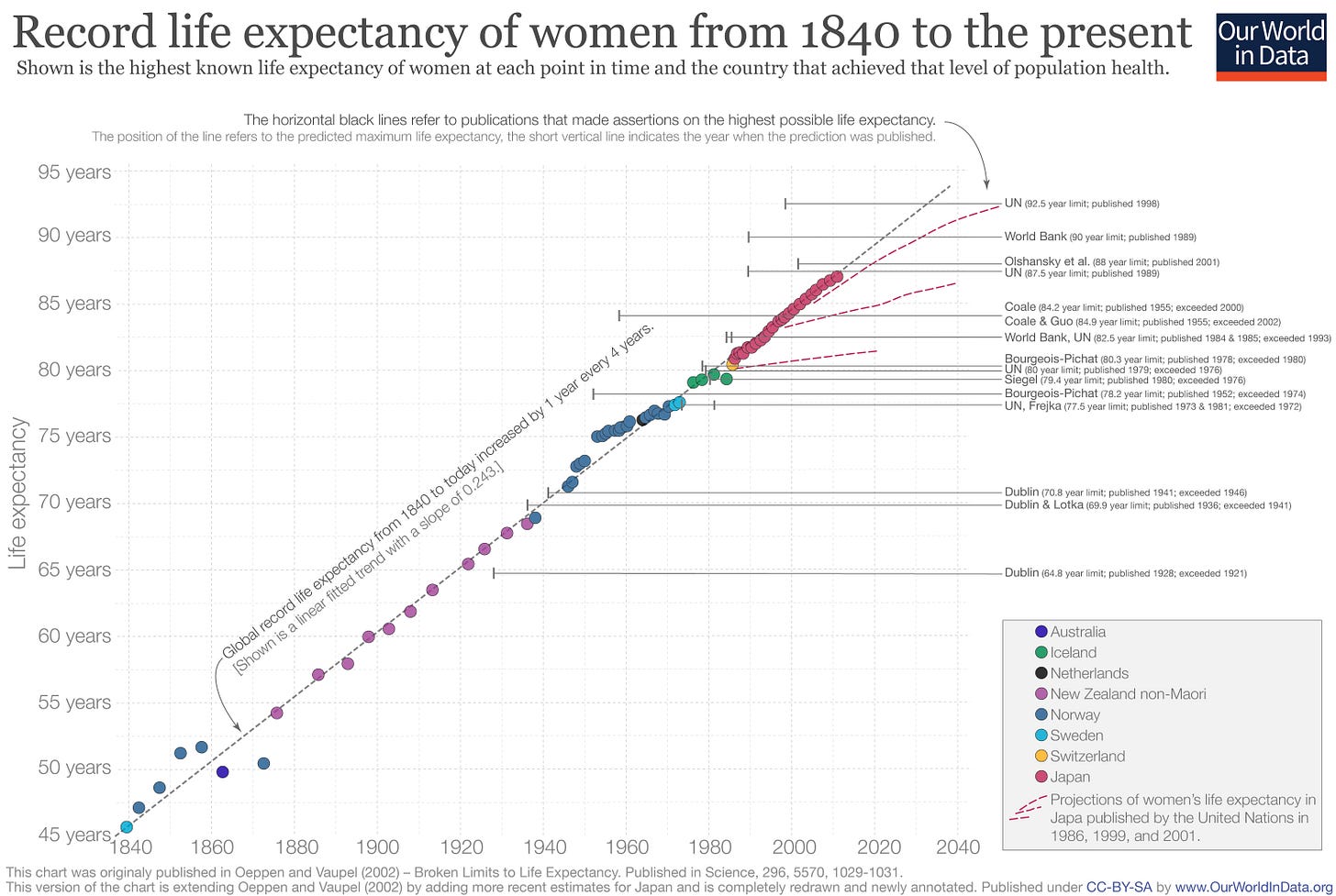

Life expectancy has been rising at a historically unprecedented rate for over a century. According to Oeppen and Vaupel (2002), the highest recorded female life expectancy among nations has increased linearly for over 160 years, at a steady rate of about 3 months per year since 1840.

Has that trend been maintained since 2002? Is it plausible to expect it to continue in the future? Gerontologists and biodemographers disagree. Some, such as Vaupel and Austad, see no obvious limit to future gains. Others, led by Olshansky, expect gains to slow down.

Figuring out who is most likely to be right helps us determine the odds of each age group putting off the need to go into biostasis. According to the most optimistic view embodied in the idea of longevity escape velocity (LEV), some of us will live long enough to reach a time when the mortality rate will fall rapidly, giving us a chance to live for at least decades longer.

Before diving into the details, it helps to first define “maximum lifespan.” (The chart below uses the term “maximum life expectancy” synonymously with “maximum lifespan.”)

Maximum life span is a measure of the maximum amount of time one or more members of a population have been observed to survive between birth and death. For humans, maximum life span is often used to refer to the age at which the oldest known member of a species or experimental group has died. For our species, assuming records are reliable, that maximum is a little over 122 years (Jeanne Calment). With respect to animals, maximum span is often taken to be the mean life span of the most long-lived 10% of a given cohort. This provides a more stable and statistically meaningful benchmark for longevity research.

For human populations today in high-income countries, the mean age of death for the longest-lived 10% generally ranges from approximately 90 to 100 years, with common estimates being around 95 years. (Women: ~95–100 years. Men: ~90–95 years.)

Predictions of life expectancy hitting a limit have been persistently too pessimistic

In their 2002 Science paper, “Broken Limits to Life Expectancy,” Jim Oeppen and James W. Vaupel show that forecasts for maximum life expectancy have been repeatedly exceeded. Sometimes the forecast has been exceeded even before the paper with the forecast was published. They refer to “the pernicious belief that the expectation of life cannot rise much further” and present data to dispute this belief.

They provide three reasons to doubt these proximate longevity limits. First, experts’ assertions that life expectancy is approaching a ceiling have been repeatedly proven wrong. Second, the appearance of life expectancy leveling off is misleading and results from laggards catching up and leaders falling behind. Third, if life expectancy were nearing a maximum the increase in the record expectation of life should be slowing but that is not happening. The remarkable picture we see is of a period of 160 years in best-performance life expectancy has steadily increased by a quarter of a year per year.

That paper was published 23 years ago. What has happened since? Our World in Data updated the chart to 2020.

That chart shows the trend persisting. Japan’s female life expectancy increased from 86.3 years in 2002 to 87.7 years in 2019. This supports the 0.24-year annual increase Oeppen and Vaupel identified.

Dublin published a study in 1928 that asserted that the maximum life expectancy possible was less than 65 while at the same time life expectancy in New Zealand was already over 65. The predictions of maximum life expectancy were proven wrong again and again over the course of the last century. On average the predictions have been broken within 5 years after publication.

Dublin’s 64.8 year limit, published in 1928, had already been exceeded in 1921. Dublin went on to make more ill-fated forecasts. His 69.9 year limit published in 1936 was exceeded in 1941, and his 1941 limit of 70.8 was exceeded in 1946.

Dublin and colleagues are far from alone in being much too pessimistic. A UN study published in 1973 and revised in 1981 predicted a limit of 77.5 years, a number that was exceeded in 1972. Siegel’s limit of 79.4 years was exceeded three years before its publication! The UN managed the same blunder when they published a limit of 80 years in 1979 when that limit was surpassed in 1976. The World Bank’s 1984-5 prediction was overtaken in 1993.

So, we can look forward to a continued rapid gain in life expectancy, right? Maybe not. It is hard to evaluate the trend of the last five years because of the effects of COVID-19. Japan’s female life expectancy rebounded from the pandemic to hit a new high of 87.8 years in 2023. Adjusted for the pandemic, that suggests a continuation of the 0.24-year annual gain. Globally, the best-performing countries (e.g., Japan, Switzerland, South Korea) continue pushing the frontier, with South Korea’s female life expectancy nearing 87.5 years by 2023.

As an aside: I have some doubt about the longevity claims for Japan and other places. A large amount of fraud and false records has turned up, showing that many very old people died many years ago. It is not clear whether the records have been cleaned up nor how much difference that would make.

Falling short of longevity escape velocity?

You are probably familiar with the concept of “longevity escape velocity (LEV).” LEV is a situation in which one’s remaining life expectancy (not life expectancy at birth) is extended longer than the time that is passing. In other words, for each year that passes you gain more than one year of life.

“Longevity escape velocity” was coined by Aubrey de Grey based on David Gobel’s concept of “actuarial escape velocity.” In 2021, de Grey said: “I now think there is a 50% chance that we will reach longevity escape velocity by 2036.” After that point […] those who regularly receive the latest rejuvenation therapies will never suffer from age-related ill-health at any age.” He estimates the chances of a 53-year-old reaching LEV to be 40% to 50%.

However, several researchers have argued that improvements in life expectancy have decelerated and are likely to continue to do so and eventually to stop altogether. Jay Olshansky and Eileen Crimmins see a “soft limit” of 83 for men and 89 for women based on the lowest death rates across ages. They argue that maximum life expectancy is nearing a plateau and the gains will slow or stop near 87–90 years.

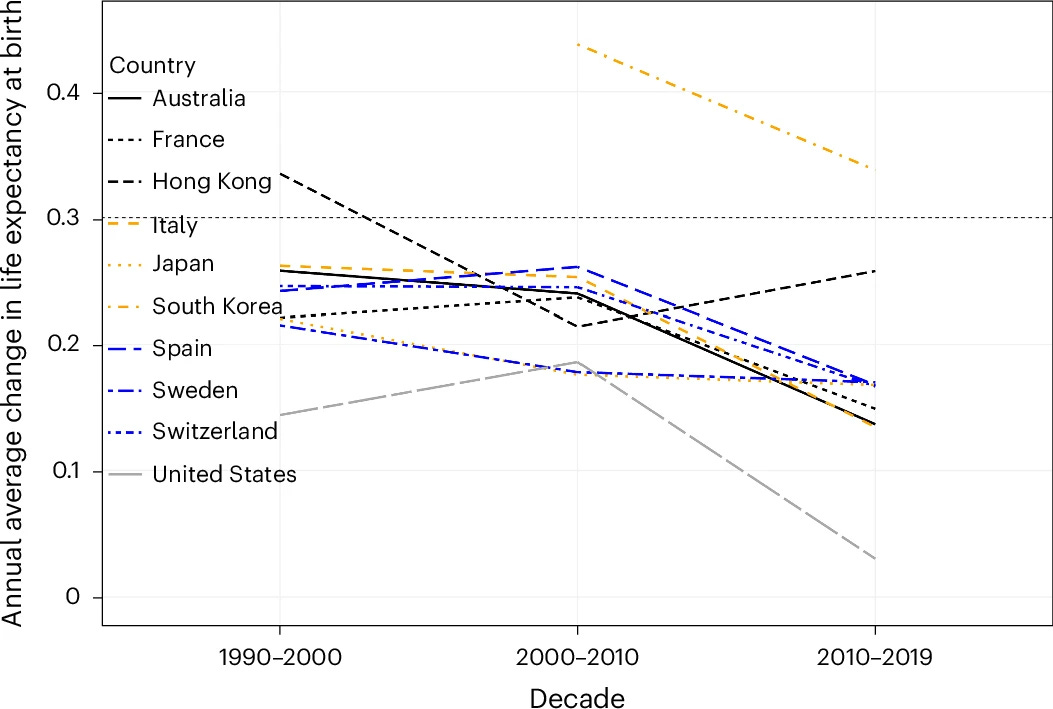

Many developed nations have indeed seen life expectancy level off in the low-to-mid 80s. Gains have slowed since 1990, with life expectancy improvements falling from 2.5 years per decade pre-1990 to 1.5 years in the 2010s, with the U.S. showing almost zero gain. Many developed nations have indeed seen life expectancy level off in the low-to-mid 80s. This results from saturating gains from vaccines and sanitation, diminishing medical gains, a rising tide of late-life diseases – more diseases appear as you get older, and from hitting the bodies “warranty period” beyond which organs and cells irreversibly deteriorate.

Vijg and Le Bourg agree that human longevity is hitting a natural limit. In their 2016 Nature paper, they demonstrated that survival improvements drop off after age 100. They note that no one has beaten Jeanne Calment’s 1997 record of 122 years, which suggests, they claim, a hard ceiling around 115 years for human lifespan.

Biodemographers Leonid Gavrilov & Natalia Gavrilova also see a recent deceleration in maximum lifespan gains. In analyzing mortality at extreme ages, they found that while death rates at younger ages have fallen significantly, centenarian mortality has not improved in recent decades. Some researchers had observed an extreme-age mortality plateau where death rates level off at very late ages. However, newer data suggest mortality continues to rise for centenarians, limiting further lifespan extension.

The divergence in views between these experts has less to do with past trends – even the more optimistic of them often recognize a recent slowdown – than with what they believe we can reasonably expect in future. Olshansky thinks that “survival to age 100 years is unlikely to exceed 15% for females and 5% for males.” However, that comes with a caveat: “unless the processes of biological aging can be markedly slowed.” Olshansky thinks geroscience might offer a “second longevity revolution” but we will not see that happen anytime soon. Stephen Austad agrees on the recent past but thinks we can do better in the future. He and Olshansky have a bet on who will be right. We will need major advances in gerontology.

Speculation for 2025–2055

When experts disagree it’s hard to know what to expect. What we can do is set out some scenarios, weighing historical patterns against emerging factors, and keep an eye one events to see which one is tracking events.

Continued Linear Growth (Base Case)

If the 0.24-year-per-year trend holds, maximum female life expectancy could reach 93.7 years by 2045 and 96.1 by 2055. This assumes steady improvements in healthcare (e.g., cancer treatments, cardiovascular care), nutrition, and public health, as seen historically. It will require tech-driven medical advances—like AI diagnostics or gene editing (CRISPR)—to sustain this. Such innovations might keep pushing mortality down at older ages, where gains have concentrated since the 1990s.

Plateau or Slowdown (Pessimistic Scenario)

Olshansky makes some good points about the previous longevity-boosting factors running out of steam. In the USA and increasingly in other wealthy countries, increasing obesity and accompanying problems like diabetes have dragged down lifespan. Antibiotic resistance could cap gains if new antibiotics are not developed. During the early 1900s, mortality reductions of around 4% were enough to boost life expectancy by a year. But now, increasing female life expectancy from 88 to 89 years would require a 20.3% reduction in mortality from all causes at all ages, the authors found, and increasing male life expectancy from 82 to 83 years would require a 9.5% reduction.

Olshansky also cites “climate stress”, perhaps because he feels it is obligatory to mention climate. This makes me less confident in his projections because climate is not a plausible factor in restraining lifespan gains. If there is any effect of warming it will be to allow the average lifespan to increase since far more people die of cold than of heat. If gains slow to 0.1 years annually, we’d see 91 years by 2045 and 92.5 by 2055 in the longest lived populations. Olshansky projects the highest rate of centenarians in Hong Kong, with 12.8% of women and 4.4% of men born in 2019 expected to reach 100.

Accelerated Gains (Optimistic Scenario)

Some demographers, echoing Vaupel’s optimism, argue breakthroughs could accelerate life expectancy gains. A paper on genetic factors in healthy aging hints at personalized medicine doubling the rate to 0.5 years annually—possibly due to senolytics or telomere therapies. If so, we’d hit 99 years by 2045 and 104 by 2055. Billionaires like Elon Musk and Sergey Brin are funding such longevity research, per 2021 reports, and small trials (e.g., metformin studies) show promise. East Asia’s rapid life expectancy rise—South Korea gained 4.1 years from 2002 to 2019—supports this potential.

LEV Soon

In an even more optimistic scenario, AI helps us figure out the aging processes and more effective ways to intervene. Instead of gaining 3 months per year, we gain 6 months, then a year per year – reaching “longevity escape velocity” – and then we put aging into reverse.

Plan A redux

Whichever of these scenarios turns out to be closest to the unfolding of actual events, accidents happen and diseases happen. Biostasis is your lifeline.

In several essays and talks I have urged against being over-optimistic about life extension research and gains in lifespan. Improvements in sanitation have extended life expectancy but these will make little difference in future. Curing heart disease or cancer will buy us only a very few years. Major breakthroughs in gerontology will be needed for us to keep going up the LEV curve. Decades of longevity research have led to zero increases in the maximum lifespan. No matter how promising current research may appear, caution is warranted. Research has appeared very encouraging multiple times in the past but did not work out.

Biostasis should be your life extension Plan A. Unlike radical longevity treatments, it is available today. Keep an eye on the research and support the research but don’t fool yourself into thinking your long-term survival is guaranteed by the promise of LEV. Protect yourself by making biostasis arrangements.

An insightful essay by Thomas Donaldson from 2004: “Why Cryonics Will Probably Help You More Than Anti-aging”

After writing this piece it occurred to me that I should mention Roy Walford’s classic book of the same title. Maximum Lifespan was published back in 1983. Despite the passage of 42 years, most of the book remains relevant. It also helps provide important historical context – especially valuable to relative newcomers who have little sense of the history of the field and who often have highly hopeful expectations for drastic near-term progress.

On a personal note, I got to know Roy in the 1990s and often talked to him at his home on Venice Beach. I asked gently about cryonics. He never rejected it but also never accepted it nor took action to make it happen. I am sad that I will never see Roy again.