Men of Good Fortune/The Sound of Her Wings

An unusually hopeful story about a very long life without death

In my previous essay, I looked at the treatment of biostasis in written science fiction. It was a mixed bag. Indefinite lifespans (often incorrectly called “immortality”) may have worse treatment than cryonics. Radical life extension or agelessness usually gets portrayed negatively. One wonderful exception to this tendency is found in a story by Neil Gaiman.

Gaiman has written many well liked stories, several of which have been made into movies or TV shows. In addition to The Sandman, these include American Gods, Neverwhere, Good Omens, Coraline, Anansi Boys, and The Graveyard Book. Personally, I have quite limited interest in stories labeled “fantasy” but have enjoyed Gaiman’s work. I was happily surprised by his story of what happens to someone granted indefinite respite from death.

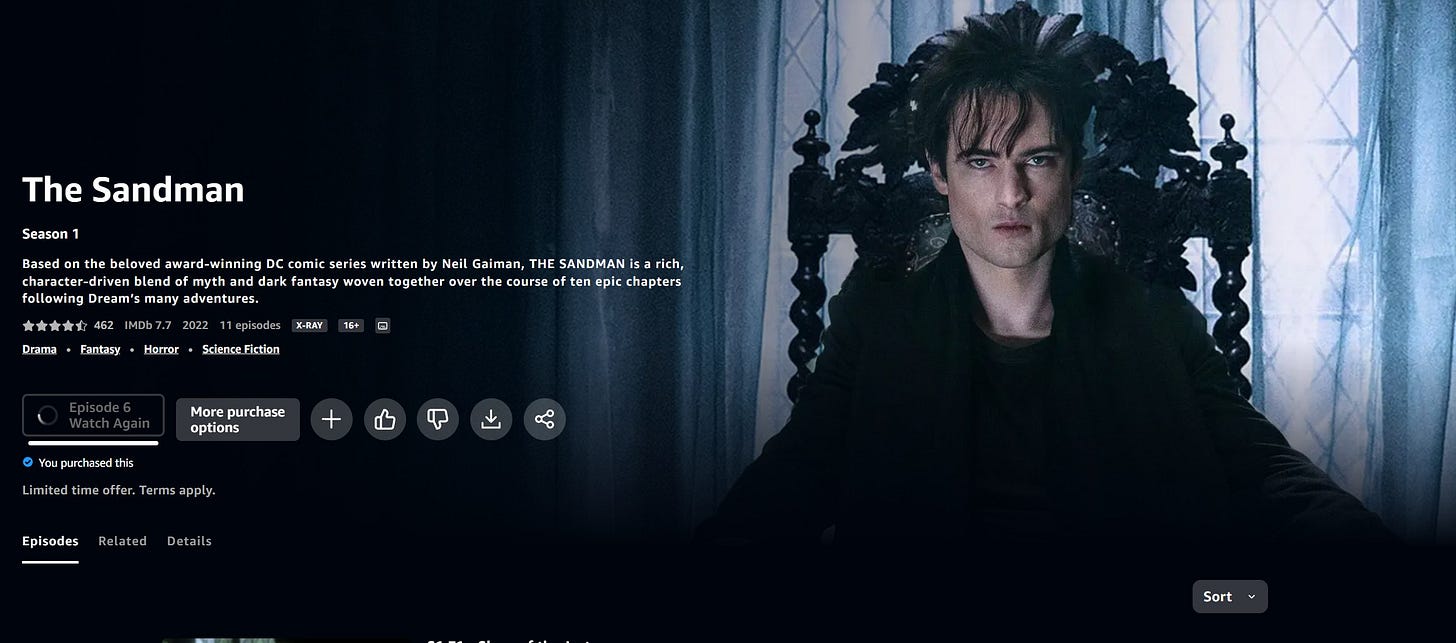

I am mainly going to relate the story as it originally appeared in the comic book Sandman #13 as “Men of Good Fortune” back in 1990. However, the 2022 TV episode follows the original closely but not exactly. The entire episode – season 1, episode 6, “The Sound of Her Wings” is excellent. But it contains two stories. If you want to skip to the story from the comic, jump to right about 21 minutes in.

To enjoy the story you need little background. The Sandman series relates the experiences of the ageless, anthropomorphic personification of Dream that is known by many names, including Morpheus. Dream is of the Endless – personifications of mythical archetypes – including his sister Death, along with Desire, Destiny, and Delirium.

SPOILER WARNING: I will reveal the plot and the ending! I don’t think it will greatly reduce your enjoyment of the story but, if you think it will, go and read or watch it before continuing!

To summarize in the extreme: It is a story about a commitment to life and an appreciation of everything about it. It is a story of a slow-burning friendship. In 1389 a man is granted agelessness and deathlessness. We follow him as he asked every century if he wants to continue living.

A man walks into a pub. That sounds like it could be the start of a joke. In this case, two personifications of mythical archetypes walk into a pub in 1389. Death wants her brother Dream to observe humans up close and to be less aloof. We hear the conversations in this 14th century public house and close in on Hob Gadling lightheartedly arguing with his table companions. He has declared that he has no intention of dying. Dream and Death listen in.

One of them says, “You are a fool, Hob. Death come to every man. Thirty years, if he escapes the plague, or the flux [dysentery], or the French. Sixty years, with fortune, and if God is willing. Then they put you in the ground to await the day of judgement.”

It’s rubbish, death. It’s stupid. I don’t want nothing to do with it.

Among Hob’s responses: “There you go – proves me point. All I’m saying is this. Nobody has to die. The only reason people die, is because everyone does it. It’s rubbish, death. It’s stupid. I don’t want nothing to do with it…” “Yeah. Fair enough. Everyone dies, I thought (except for maybe the Wandering Jew), but why the Hell should I? I might get lucky. There’s always a first time.” “No, it’s rubbish, death is. I mean, there’s so much to do. So many things to see. People to drink with. Women to swive. You lot may die. I expect you will, ‘cos you’re stupid. Not me, though.”

Dream approaches Hob as asks: “Did I hear you say that you have no intention of dying?”

Hob: “Um. Yeah. Yeah. That’s right. It’s a mug’s game. I won’t have any part of it.”

Dream: “Then you must tell me what it’s like. Let us meet here again, Robert Gadling. In this tavern of the White Horse. In a hundred years.” In the TV version, Dream predicts Hob will be begging for death in a century.

So, they meet once a century. The background details add to the story by providing historical context. For instance, in 1489 he hears a customer talking about how people still complain even though they now have chimneys. Handkerchiefs and playing cards have also come into use. Hob has started a new business, printing, but doesn’t believe it will last. Dream asks him: “So you still want to live? Hob replies: “Oh yes.”

1589: Hob is well off. “Life is so rich.” He is now Sir Robert Gadlen.” Gaiman drops more historical events into the conversation, such as King Henry’s attacks on monasteries and the introduction of white bread. Hob has his first son in over 200 years of living. He says he has “everything to live for. And nowhere to go but up.” Dream is not that interested in his story of good fortune and becomes distracted by the young William Shakespeare whose work in held in little esteem by his mentor, the playwright Christopher “Kit” Marlowe.

Dream strikes a secret bargain with Will, who wanted to “write great plays” and “create new dreams to spur the minds of men.” We learn that Dream’s bargain with Shakespeare was the ability to spin words that will never be forgotten in exchange for two plays that celebrate dreams. Will must write one at the beginning of his career and one at the end. A Midsummer Night’s Dream was commissioned by Dream as a gift for his friends, the Faerie. The second and final play Shakespeare writes for the Sandman is The Tempest.

1689: Everything has fallen apart. Hob staggers into the pub clothed in rags. He tells Dream that his wife died in childbirth and his son died at 20 in a tavern brawl. His hunger is terrible because he cannot die. In tears, he tells Dream: “I’ve hated every second of the last eighty years. Every bloody second. You know that?”

Dream: “And you still wish to live? Do you not seek the respite of death?”

Hob: [Thinks about it.] “Are you crazy? Death is a mug’s game. I got so much to live for.”

Honestly, the scene brings tears to my eyes. Hob has suffered but wants to go on and start again. You don’t give up when life gets tough.

We can skip over 1789, with its own side-plot. In 1889 they meet again. Hob tells Dream he thinks Dream returns every century because he seeks friendship. Dream is outraged and offended. “You DARE? You dare imply I might befriend a mortal? That one of my kind might NEED companionship?” Dream exits the pub followed by Hob who tells him: “Tell you what. I’ll be here in a hundred years’ time. If you’re here then, too – it’ll be because we’re friends. No other reason. Right?” Finally, in the present, Dream shows up and accepts Hob as his friend.

This is a heart-warming story. It is also funny, historically informative, and provides an unusually encouraging view of an indefinitely long life. From our perspective looking into our future, we can probably expect much better conditions for living than Hob’s, certainly before he got to the latter part of the 19th Century when technological progress accelerated. At the same time, we should not expect a life of ease and without challenges – and I would not want one.

The television version is enriched by excellent performances by Tom Sturridge as Dream, and Kirby Howell-Baptiste as a surprisingly likable Death, but the standout is Ferdinand Kingsley – son of Ben Kingsley – who plays Hob Gadling just right.

We can locate a few other stories featuring long-lived characters who experience profound lows — grief, boredom, alienation — yet return to the conviction that life is precious. They contrast strongly with the “Tithonus” model, where immortality is always portrayed as unbearable. These include:

“The Man Who Lived Forever” (1974), R.A. Lafferty.

Time Enough for Love (1973), Robert Heinlein

The Boat of a Million Years by Poul Anderson.

The First Immortal by James Halperin.

The Tale of the Wandering Jew. (Many variations.)

“Men of Good Fortune” written by Neil Gaiman, pencils by Michael Zulli. In The Sandman #13, February 1990.

“The Sound of Her Wings.” August 5, 2022. 53 minutes. Relevant part starts at 21 minutes.

Tom Sturridge as Dream. Kirby Howell-Baptiste as Death. Jenna Coleman as Johanna Constantine. Ferdinand Kingsley and Hob Gadling. Samuel Blenkin as Will Shakespeare.