Resources for the Future: Natural vs. Human-Created

Why there are no "natural resources" and why resources are essentially unlimited

Are resources for the future of our species finite or not? Are we living on a sinking lifeboat or are we living in an expanding cloud of resources?

For those of us who want to radically extend their life – or to be placed into biostasis to return decades from now – we must have a sense of possibility about the future. We must believe that the future is likely to be a place where we will want to live. In a sense, we are optimists – practical optimists who believe the future can be better than the past and present because humans have the capability to make it so.

Rather than “optimist” – which is sometimes taken to mean a non-objective view – we might adopt Hans Rosling’s term and call ourselves possibilists. A possibilist, wrote Rosling, is “someone who neither hopes without reason, nor fears without reason, someone who constantly resists the overdramatic worldview.” When we are revived, most of us expect to enter a world of possibility supported by abundant energy and abundant resources. That makes us unlike most people.

A possibilist is someone who neither hopes without reason, nor fears without reason, someone who constantly resists the overdramatic worldview.

I have argued and debated issues of resources and the future for over 45 years. During that time resource availability has grown even as a growing global population consumed more. The population has doubled in that time and yet people are living longer, poverty has declined massively, hunger is less common, and energy has become ever more available. These statements are backed by solid evidence for all who are willing to look and yet most people believe the opposite.

Pessimists such as Paul Ehrlich have been repeatedly proven wrong and yet continue to repeat their apocalyptic falsehoods. After losing a bet to Julian Simon on the price of raw materials over a decade, Ehrlich refused to make a bigger bet and doubled down on error. Further research into the cost of raw materials over time compared to how long we have to work for them (their “time price”) has continued to strongly validate Simon’s view. You can find an excellent summary of our continued progress in the Simon Abundance Index.

Futurephobia

Repeated false messages of climate doom, AI doom, and other forms of imagined doom are discouraging people from having children. They must also be discouraging people from having supportive attitudes toward life extension. Some examples:

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in 2019 expressed concern in an Instagram video about the ethics of having children in the face of climate change. She said, “Basically, there’s a scientific consensus that the lives of children are going to be very difficult, and it does lead, I think, young people to have a legitimate question: Is it okay to still have children?”

Miley Cyrus stated in a 2019 Elle interview: “Until I feel like my kid would live on an earth with fish in the water, I’m not bringing in another person to deal with that.” The BirthStrike and No Future No Children movements encouraged people to pledge not to have children due to climate change. Abbie Chatfield, an Australian media personality, has expressed that she and her partner are unlikely to have children due to climate change fears. She shared this perspective with her followers, highlighting environmental concerns as a significant factor in their decision.

A Pew Research Center survey from 2023 indicated that 47% of U.S. adults aged 18-49 are unlikely to have children, with significant concerns about the state of the world and the environment influencing their decisions. In a 2020 study by Morning Consult, 11% of childless adults cited climate change as a “major reason” for not having children. A study published in the journal Climatic Change found that 59.8% of Americans aged 27-45 were very or extremely concerned about the carbon footprint of a future child.

These surveys reveal a consistent pattern. At the same time, I don’t necessarily believe the survey numbers. It is easy for people to say things on surveys but their actions do not necessarily match their statements. Other research that attaches a cost to climate action finds that few people are willing to pay even a tiny amount. That casts doubt on the seriousness of their worries.

There are people who argue that having children should be illegal due to (their belief that) the planet becoming increasingly uninhabitable. They suggest accelerating human extinction to prevent future generations from living in a world with water scarcity and numerous disasters.

Some individuals express panic about their own later life conditions and feel that having children would be unfair, given the decades of challenges they believe these children would face. Prince Harry mentioned in a 2019 Vogue interview that he and Meghan would have “maximum” two children due to environmental concerns about the future. Sarah Baillie, a 31-year-old population and sustainability organizer at the Center for Biological Diversity, affirmed her decision not to have children after working on environmental issues.

Many people in online forums, such as Reddit’s r/childfree or r/collapse, have shared personal stories about choosing not to have children due to fears about the future. These fears often center on climate change, political instability, economic inequality, or the belief that society is on the brink of collapse.

Although musician Grimes (Claire Boucher) has children, she has spoken about the ethical dilemmas of bringing children into a world facing existential threats, reflecting a broader sentiment among some individuals.

Resources: Natural or created?

These anti-life statements and behaviors are partly due to false beliefs in a “climate crisis” or more general “environmental crisis” but part of it is related to a belief that resources are limited (the “finite Earth”) and are about to run out. It is not just the idea that there is a finite amount of natural resources that we will use up, leading to our doom. This belief portrays humans as parasitic on the Earth and as necessarily in conflict with one another to grab a place in an ever-shrinking lifeboat.

This finitist picture is incorrect. First of all, humans are not (only) destroyers but creators. Human beings create things and solve problems. As Julian Simon noted, “Our constructive behavior has counted for more than our using-up and destructive behavior, as seen in our increasing length of life and richness of consumption.” (The Ultimate Resource II, p.74)

The crucial point is that there is no such thing as “natural resources.”

Second, the crucial point is that there is no such thing as “natural resources.” That term implies that resources are already existing quantities that we merely have to pick up. In reality, resources are services that we derive by combining raw materials with knowledge and purpose. As Simon put it:

“…natural phenomena such as copper and oil and land were not resources until humans discovered their uses and found out how to extract and process them, and thereby made their services available to us. Hence resources are, in the most meaningful sense, created, and when this happens their availability increases and continues to increases as long as our knowledge of how to obtain them increases faster than our use of them, which is the history of all natural resources.” (p.75 footnote)

When people talk about what percentage of world resources are used up by the population of the USA they fail to recognize the creation of resources. Humans have become ever better at creating resources. Consider farmland. Farmland is not a natural resource. It requires tools and work by humans to produce what we want. And metals: Before we knew how to extract and use them, the vast amounts of tin, lead, iron, aluminum and other metals were not resources, they were merely materials. Neither oil nor gas nor petroleum were considered resources until humans saw how to use them to produce value and added our knowledge to turn minerals into resources.

Humans are a resourceful species. Even as we use resources we are constantly creating more.

Before we developed nuclear power, uranium and thorium deposits were not resources. With nuclear and solar, we look forward to an essentially unlimited future supply of energy. Robert Zubrin understands this point well as he shows in discussing resources on Mars. “There is no such thing as a natural resource. There are only natural raw materials. It is human ingenuity, manifested as technology, which transforms raw materials into resources.” People talk about the “carrying capacity” of the Earth. As Zubrin asks: “So, what is it that ‘carries’ us? It is not the Earth. It is human ingenuity. We are the authors of the resources that now sustain us. We will create much more.”

Dematerialization and superabundance

How much stuff is left for humans to use? This is not a particularly useful question. Even if we could answer it we would have little idea of the availability of the resources that could be created from the raw materials. Thinking of an actual number of a material is problematic because it suggests that there is a fixed amount of some uniform material. But even focusing on pure quantities rather than resources, we get wildly differing answers depending on what definition of “resources’ we are using. There are “known (or proven) reserves,” technically recoverable resources (TRR), economically recoverable resources (ERR), ultimate recoverable resources (URR), and total crustal abundance (TCA).

People who proclaim imminent doom from resource scarcity – such as the infamous 1972 report Limits to Growth – typically focus on known reserves. These people project “years of consumption left” by dividing the “known reserves” by the current rate of use. This is what is called a technological forecast, as distinguished from an economic forecast. Measuring quantity of resources is almost useless.

As Tupy and Pooley, the authors of the excellent book Superabundance, explain, the apparently objective fact of reserves is not as clear as it seems (p.107-8). We often cannot directly observe the materials we are interested in. For instance, we do not know how much oil and gas in total exists in our planet. In addition, these materials are not all interchangeable. Instead, commodities come in a variety of grades and concentrations. This makes it difficult to estimate costs of discovery, extraction, and refinement. Complete surveys of commodities are not undertaken because they are very expensive. We find more as we look more. Sometimes we discover vast new reserves completely unexpectedly.

A number denoting the quantity of a material seems like an objective accounting but it fails to allow for recycling and substitution. Another source of uncertainty comes from difficulties in predicting new discoveries of deposits and new extractive technologies that increase the supply. For instance, horizontal drilling enabled us to extract much more from what were previously considered exhausted supplies. Fracking has had the same effect. Commodity reserve estimates may be set low because overestimating will cost a company dearly. In contrast, underestimating means the company will not explore, thereby saving money with the cost (foregone growth) being unseen.

The concept of proven reserves is helpful to companies in their planning for the next few years. But it tells us nothing useful about our resource future. Proven reserves estimate how much of a raw material can be extracted at current prices and with current technologies. If prices rise, it becomes profitable to spend more to find and extract more and to develop new techniques and technologies. Innovative technologies can vastly expand the resources we can create. Forecasts based on proven reserves do not allow for these powerful factors. They also give a misleading impression of rapidly depleting reserves because we will naturally mine for the most promising lodes first.

A fascinating application of the idea that resources are human creations and not objective and limited quantities comes from the phenomenon of dematerialization — the decoupling of economic growth from growth in resource usage. Relative decoupling is common. This means we use less of a material per capita. For instance, our current automobiles use far less metal than older cars as do our cans; our smartphones replace dozens of other gadgets and tools. Absolute decoupling is less common but seems to be spreading. This is a reduction in the amount of a material used by a country. In other words, not only are people using less of a material individually, so is the entire nation even though its population may be increasing.

We are seeing this decoupling of economic value from physical quantities not only in how much we use but in how much we pollute.

In wealthier countries we have seen a drop in total pollution measured in multiple way and some countries even show evidence of energy decoupling. Decoupling of economic value and raw material usage happens because we slim down our products (cars and cans), swap one material for another, use materials more efficiently, or do away completely with a material by providing the same service by other means.

Such is the distorted view presented by mainstream media that when I tell people that pollution in developed countries has been dropping for decades, they don’t believe me. Yet the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finds these changes in major pollutants from 1980 to 2018:

Carbon monoxide down 73%

Lead down 99%

Nitrogen oxides down 62%

Compounds from automobile exhaust associated with ozone down 55%

Sulfur dioxide down 90%

Particulates down 61%

Between 1970 and 2017, the combined emissions of six common pollutants (PM2.5 and PM10, SO2, NOx, VOCs, CO, and Pb) dropped by 73%. Aggregate emissions fell 74% from 1970-2018. [EPA]

In his book, More from Less, Andrew McAfee points out that in the USA we reached “peak metal” around 2000. Since then, copper consumption has declined more than 40%, aluminum by 32%, and steel by 15%. The depletion of wood seen during the last century has stopped and reversed, with an increase of 36% in the volume of wood on American timberland since the middle of the last century.

Out of 100 commodities, 36 had peaked in absolute use and another 53 commodities had peaked relative to the size of the economy but were still growing in total. Most of those “now seem poised to fall”. At the time of this study, only 11 of the 100 commodities were still growing in both relative and absolute use. In the case of nine basic commodities, absolute use was flat or falling for about 20 years.

Energy is the master resource. So long as we have abundant, affordable energy, we can use it to make other resources more available. We may be able to do that to an extent without increasing total energy consumption. U.S. energy consumption per dollar of GDP declined nearly every year since 1949. Total energy consumption in some European countries has decreased in total although it is unclear how much of that is a positive development or a result of bad energy policy. Whether or not that trend continues, our future depends on our ability to generate plentiful energy.

So long as destructive energy policies do not dominate, we will have no shortage even looking far into the future. We capture only a tiny fraction of the solar energy reaching the Earth and none of the enormously greater amount pouring into space. The Sun emits approximately 3.8 x 1026 watts of energy. The Earth receives approximately 4.53×10−104.53×10−10 (or about 0.0000000453%) of the Sun's total solar output. The Earth receives about 1 part in 2.2 billion of the energy emitted by the Sun. In billions of years when the sun dies, we can look to other suns.

The Earth receives about 1 part in 2.2 billion of the energy emitted by the Sun.

Nuclear fission and fusion can supply us practically forever. Abundant energy enables increased substitution between materials. Materials abound beyond “Spaceship Earth.” We will eventually tap resources in our solar system outside of Earth beginning with the Moon and asteroids.

Reserves growing

We often hear not only about “peak x” (often oil) but also that we will soon “run out” of a raw material such as oil or coal. At the time of the first Earth Day in 1970, ecologist Kenneth Watt declared, “By the year 2000, if present trends continue, we will be using up crude oil at such a rate… that there won’t be any more crude oil. You’ll drive up to the pump and say, `Fill ‘er up, buddy,’ and he’ll say, ‘I am very sorry, there isn’t any.’” Watt was not the first. In 1919, the U.S. Geological Survey warned that world oil production would peak in 1928.

In 1980, global proven reserves were estimated at 684 billion barrels – about 30 years supply at that year’s rate of extraction. We have since extracted 983 billion barrels, but proven reserves have nearly tripled to 1.7 trillion barrels – enough for 50 years at the current rate.

Gas reserves have also increased:

Limits to Growth got it wrong. The projected exhaustion of various minerals never happened. The authors of Limits projected the exhaustion of aluminum, copper, gold, lead, mercury, molybdenum, natural gas, oil, silver, tin, tungsten, and zinc by 2013. And yet commodity prices have generally fallen to about a third of their level 150 years ago.

In fact, no exhaustible resource is essential or irreplaceable. The price mechanism not only spurs investment in discovering new reserves of a resource, it also stimulates conservation and substitution. A deeper point that the limitationists or depletionists fail to grasp is that what counts as a resource changes over time. The shipbuilding industry relied primarily on wood until the 1800s. People had started worrying that wood would run out back in the 1500s. Instead, boats were made of iron and steel, and then wood became plentiful again.

We will never run out of materials such as copper because its price will increase as it becomes scarcer, stimulating the discovery of more deposits, more recycling, new methods that use less of it, and better substitutes.

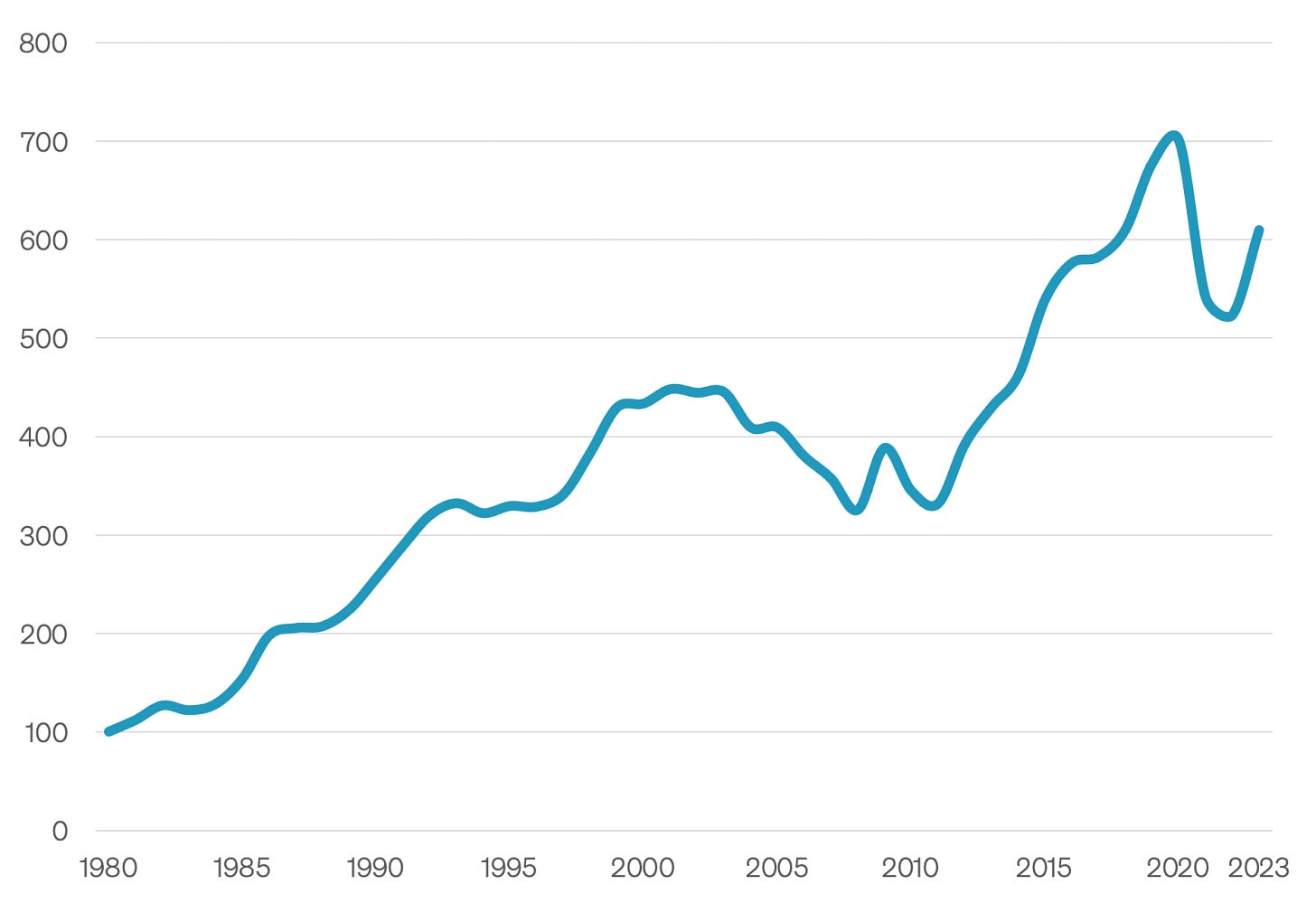

Over at the highly recommended Human Progress.org website, the Simon Abundance Index (SAI) measures abundance in terms of the number of hours we must work to acquire to acquire something. This is a better measure than nominal price – which fails to account for inflation – and better even than inflation-adjusted (real) prices. Real prices may increase but if income goes up more then in the most important sense goods are cheaper.

The Simon Abundance Index 2023

The SAI (updated annually) shows that the Earth was 4.2 times as plentiful in 2022 as it was when Ehrlich and Simon commenced their wager. In terms of the Abundance Framework, we are experiencing superabundance – “a condition where abundance is increasing at a faster rate than the population is growing”. We have seen a compound annual growth rate in resource abundance of around 5% and doubling of global resource abundance every 14 years or so. 50 common raw materials have become less scarce over the last forty years when we adjust for inflation and increases in income.

Abundance has increased by over 500% since 1980. All 50 commodities measured were more abundant in 2023 than in 1980. In terms of time worked, these 50 basic commodities fell in cost by over 70%. Put another way, in 2023 you could buy well over three times as many units of these commodities for each one in 1980.

The SAI uses standard, widely accepted sources for its numbers. Our World in Data agrees. Looking at global proven reserves for the period 1980-2021, it finds increases of 158% for crude oil, 181% for gas, and 17% for coal.

No limits

The idea that resources available to us are essentially unlimited is not intuitive. We are too used to the idea of a fixed quantity sitting in a container that we only deplete. But markets and technological progress are enabling us to tread more lightly on the planet rather than using it up at an accelerating pace. As Jonathan Adler puts it, “The Malthusian “limits to growth” have not merely been delayed or forestalled; they have been transcended.”

By the time any of us are revived from biostasis, humanity will likely have expanded well beyond this planet. We will be extracting raw materials from the Moon, Mars, and the asteroids, combining them with our knowledge to turn them into resources. The asteroid belt is estimated to contain $700 quintillion worth of resources. The Davida asteroid is estimated to contain $27 quintillion of platinum, iron, nickel, and other precious metals. That is $27,000,000,000,000,000,000. [Maxey, 2017; Yarlagadda, 2022]

Looking further into the future, we might also factor in the effects of nanotechnology in whatever forms it takes. The ability to control matter on the atomic level would make reuse and recycling drastically more advanced than it is today. If we move more of our business and personal activity to virtual environments (as these begin to rival physical reality in their richness), fewer physical resources will be needed, with the possible exception of energy to run the computers.

We can have indefinitely long lives without ever running out of resources. Do not allow the faulty logic of the doomsayers to go unchallenged.