Some love apparently mathematical or logical arguments that lead to a conclusion with certainty. You can see this among AI doomers. There are also arguments that claim to prove things by pure logic such as the ontological argument for the existence of an omnipotent, omniscient, benevolent God. (Alvin Plantinga even provides a model logic version. It looks impressive but is no more persuasive.) Pascal’s Wager is one of these. A structurally similar argument has been presented in cryonics, concluding that it is always rational to choose to undergo cryonics (or biostasis more generally).

Does Pascal’s Wager work? Whether or not it works, does the Cryonics Wager work? If not, does it give more reason for making the decision to go into biostasis than Pascal’s argument compels us to believe in God?

Pascal’s Wager is a philosophical argument presented by Blaise Pascal, a 17th-century mathematician, physicist, and philosopher, in his work Pensées. The wager aims to justify belief in God, not through direct evidence of God’s existence, but through a cost-benefit analysis of belief versus disbelief.

His argument is interesting because it is not a typical deductive argument for God (as in the cosmological argument and argument for design), nor a moral argument (Kant, Sidgwick), nor an argument based on the meaning of words (ontological argument), nor an inductive version of the standard arguments (as best represented by my philosophy of religion tutor at Oxford, Richard Swinburne). J.L. Mackie in his masterful book, The Miracle of Theism, categorizes it as a version of “belief without reason” – other forms of which you can find in William James and Emil Kierkegaard.

We know that belief without reason is possible. In fact, it’s common. What is interesting, as Mackie puts it, “is rather the paradoxical question whether belief without reason may none the less be intellectually respectable, whether, although there are no reasons which would give a balance of direct support to theistic doctrines, there are reasons for not demanding any such reasons.”

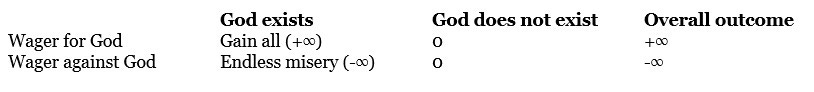

Either God exists or he does not. Pascal believes that reason cannot decide the question either way. You cannot simply suspend judgment. The only option left to you is to gamble, to place a bet on the side of belief or the side of non-belief. The outcome of your decision will have profound consequences. What are your interests that you put at stake with this gamble? On the positive side, you could gain knowledge of the truth and absolute, infinite happiness.

On the negative side, you risk error and eternal misery. Your reason makes the choice and your will enforces the belief. The gain of winning is infinitely good. The cost of losing is infinite pain. Despite the lack of any intellectual reason to believe that God exists, you have a powerful practical reason to bet on God existing. No matter how unlikely God’s existence, the calculation is overwhelmingly dominated by the infinities of happiness and suffering. Pascal presents belief in God as a rational choice because the potential reward (infinite happiness) outweighs any finite cost of belief, even if the probability of God’s existence is uncertain or small. Basically, you are doing a cost-benefit analysis. The sensible choice seems clear!

Mackie formulated Pascal’s Wager as a decision matrix but the version in Edward McClennen’s 1994 book chapter, is clearer as is the version in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. My version is this:

It has been suggested that Pascal actually presents four versions of the argument, but I’ll keep things simpler here.

The argument is superficially compelling. Most critics even grant that the argument is logically valid. (For non-philosopher: “valid” here means the conclusion logically follows from the premises, not the common usage meaning of valid = correct.) In other words, if you grant Pascal’s assumptions, the argument succeeds. But should we accept those assumptions?

Ah, but!

One objection that springs to mind is that, no matter how compelling the argument may be, you cannot simply will yourself to believe something. Our minds do not come with a “believe!” button that we can press. However, it is much more plausible to say that you can come to believe by deciding to cultivate belief. You can avoid thinking of the objections, you can surround yourself with believers, and you can engage in rituals based on the belief. Eventually it may become “second nature.”

Even if we grant this, there remains a problem of inauthenticity of belief. Genuine belief cannot be forced or based on pragmatic reasoning alone. Critics argue that “betting” on God’s existence for personal gain does not result in true faith, which many religions require for salvation. Also, Pascal seemed not to consider that God may punish you for trying to believe in him out of coldly calculated self-interest rather than genuine belief. “The sort of God required for Pascal’s first alternative is modeled upon a monarch both stupid enough and vain enough to be pleased with self-interested flattery.” [Mackie, p.203] If there is a God, perhaps he prefers an honest doubter to mercenary self-manipulator.

Pascal claims that the cost of belief is small. In reality, it might require significant sacrifices—time, resources, lifestyle changes—that some see as substantial costs, especially if the belief turns out to be false. He suggests that his wager does no damage to your reason since, he says, reason cannot decide one way or the other. But working to set aside your reason and believe something purely due to a calculation is to abandon reason and to do yourself intellectual damage. This point, presented in a more favorable light, tells us: “To acquire faith, you must become as a little child.” But we grow up and put aside childish things – and childish beliefs.

An especially fatal counterargument is sometimes called the “many gods” objection. Pascal’s Wager assumes a binary choice between belief in the Christian God and atheism. However, there are countless possible gods and religions, each with its own set of rewards and punishments. Believing in one god might alienate another, making the wager far less straightforward. You might piss off Kali or Odin or another of the truly horrible gods humans have envisioned. In an episode of South Park, this is exactly what happens. At the gates of Hell, devout people are confused until they learn that the Mormons were right and everyone else was wrong, and God condemns those who got it wrong.

Perhaps it is not enough to believe in the right God. Perhaps, as many sects insist, you have to believe in the right God in the right way. Maybe you have to be Catholic. Or Anabaptist. Or Greek Orthodox. Or Pentecostal. A related point: Pascal’s argument is deeply rooted in a Christian framework. Critics from other cultural or philosophical traditions might find the assumptions and framework irrelevant to their worldviews.

Some religions and some variants of Christianity affirm the idea of predestination—the belief that God has foreordained all events, including the eternal destiny of human souls. If true, that would make betting pointless.

The Cryonics Wager

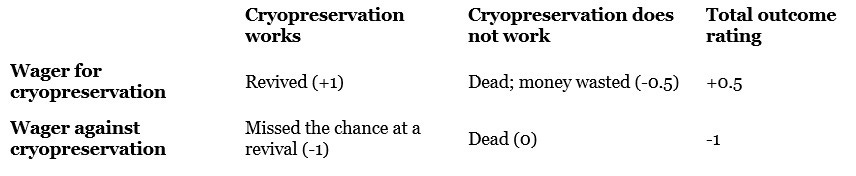

I will use this name since it is how it has been known. Clearly, though, it could be called the “Biostasis Wager” since the particular means of reaching a future without aging is unimportant. This argument originates with Ralph Merkle and is inspired by Pascal’s Wager. This wager has nothing to do with choosing to believe in a god. It is an argument that the rational and prudent choice is to undergo biostasis with the possibility that the future may revive you rather than choosing to let yourself die. This is the basic idea:

If cryonics works and you choose it, you may achieve a form of extended life in the future, a life that could endure for a vast number of human lifetimes.

If cryonics works and you don’t choose it, you lose your chance at revival and any possibility of future life.

If cryonics doesn’t work, the outcome is the same whether you choose it or not—you remain dead permanently.

Given these possibilities, choosing cryonics is seen as a rational bet because the potential reward (extended life or revival) far outweighs the potential loss (money spent on the procedure, which would not matter if you’re permanently dead).

Unlike Pascal’s, the Cryonics Wager does not rely on an infinite reward or cost. Whereas God is not something amenable to empirical or rational support, biostasis is supported by growing evidence and a reasonable projection of future repair capabilities. Both arguments emphasize the asymmetry between the potential rewards and costs. The upside in Pascal’s version is infinite. The upside in the cryonics version is not infinite (probably) but is potentially extremely large. The cost of being wrong in Pascal’s version is infinite misery. In the cryonics version it is the loss of an indefinitely long future existence. Biostasis is a true form of life insurance. You pay a modest amount to avoid a major downside, personal extinction.

If biostasis does not work and you will never be revived, what have you lost? We cannot honestly say that if biostasis doesn’t work, the individual would be no worse off than they would have been without it. They will have had to pay membership dues, provide funding for the process, and will incur the effort of making arrangements and ensuring they stay in place. There may also be costs in terms of hostile social reactions. Some argue the money might be better spent on improving life quality or advancing science during one’s lifetime. This is a fair point. Hence the value in trying to assess even approximately the chances of biostasis working for you – see “What is the probability of cryonics working?”

Whereas Pascal can promise infinite bliss, biostasis opens up the possibility of living in a future of unknown character. If that future has the means and the will to repair and revive us, it probably won’t be a disastrous future. But we could have trouble adjusting and adapting. This makes the calculus far more uncertain than in Pascals’ Wager (given his assumptions). How do we even attempt to calculate the pluses and minuses of the future? Perhaps it will be fantastically good, with human problems largely solved, with endless adventure, pleasure, and discovery. Or perhaps it will remain a struggle, worthwhile but not overwhelmingly.

Finally, what value – positive or negative – should we assign to our experiences a century, a millennium, a million years in the future? Will we be the same person as we are today in the relevant sense? Should we value an experience of our far future self equally with such an experience today or should we discount it based on the growing differences between us-now and us-then?

In conclusion, while Pascal’s Wager and the Cryonics Wager share structural similarities as cost-benefit analyses under uncertainty, their foundational assumptions and implications are profoundly different. Pascal’s Wager relies on infinite stakes tied to metaphysical claims that are not empirically verifiable and often demand a suspension of reason. In contrast, the Cryonics Wager, though speculative, is rooted in scientific plausibility and offers a finite yet potentially immense reward—continued existence in a possibly advanced future. The Cryonics Wager avoids some of Pascal’s pitfalls, such as reliance on infinite outcomes and unverifiable premises, but introduces its own complexities, including ethical, logistical, and philosophical uncertainties about identity and future quality of life. Ultimately, both wagers prompt us to confront the limits of our reasoning, the weight of our choices, and the value we place on the unknown.

Well, to be completely thorough there is also the possibility cryonics works but the future is worse than death … https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Have_No_Mouth,_and_I_Must_Scream 😱

Might also be fun to bring up the how cryonics can be considered from the hypothetical quantum suicide thought experiment perspective.